Sage and Sand: Pushing Nevada Water Law Toward Conservation

We scored a big win at the Nevada Supreme Court, which will help advocates defend wildlife and water for generations to come

Greetings friends, and welcome to another edition of Sage and Sand. I’ve devoted this entire edition to an exhaustive look at the recent Supreme Court ruling in Sullivan vs. Lincoln County, and its ramifications on Nevada water law going forward. If you’re totally uninterested in the details of Nevada water law, you may choose to skip reading this edition. Don’t worry, we’ll be back to our regularly scheduled programming soon.

Before reading my ramblings, you may want to read the news about the ruling here:

Inside Climate News, The Nevada Independent, Associated Press, Las Vegas Review-Journal

Now, without further adieu… 4000 words on Sullivan v. Lincoln County.

And just like that, one day everything changes.

The Nevada Supreme Court ruled in Sullivan v. Lincoln County last week, and they set off an earthquake that shook Nevada water law to its core. How to manage interconnected sources of water, and whether the Nevada State Engineer even has authority to do so, have been definitional questions in Nevada water law for over a decade. The Supreme Court gave a definitive, unquestionable answer: the state of Nevada has the authority to manage interconnected sources of water as a single source in order to protect senior water rights and wildlife. Period.

In many ways, Nevada water law can now be thought of as Pre-Sullivan and Post-Sullivan. Pre-Sullivan, nearly every fight involving groundwater centered around legal questions as to the interconnectedness of ground and surface water resources, and to the State Engineer’s authority to manage such resources conjunctively. Now, the question of the State Engineer’s authority has been definitively settled. In a Post-Sullivan world, conjunctive management is the law of the land. Now we can stop arguing about whether we should act to stop groundwater overappropriation; whether obviously interconnected sources of water can be managed as a single resource; now we can start moving forward with how we should act to resolve conflict between water users and with environmental values including wildlife.

Background

The case in question is called the Lower White River Flow System (LWRFS) and primarily affects a seven-basin aquifer system in southern Lincoln County and eastern Clark County. The impetus for the case is Coyote Springs, a proposed city of 250,000 people in the desert sixty miles northeast of Las Vegas. In order to be viable, Coyote Springs’ developers need water, and lots of it. While at one time they planned on siphoning water off of the ill-fated Las Vegas pipeline proposal, now they are totally reliant on applications they’ve made for groundwater pumping for their proposed city’s future.

However, the groundwater they’re trying to access is already spoken for. Coyote Springs Valley is part of an series of hydrographic basins which are perched atop an interconnected carbonate groundwater aquifer, which is now referred to as the LWRFS. Down-gradient from Coyote Springs Valley in the LWRFS is the Muddy River, a spring-fed and short river which flows from its headwaters at springs in Moapa Valley through the communities of Logandale and Overton before spilling out into the Colorado River at Lake Mead. The Muddy River supports numerous endemic biota including the Moapa dace (Moapa coriacea), which is federally listed as endangered. The Muddy River, as it reaches Lake Mead, also comprises part of Las Vegas’s water supply, because the Southern Nevada Water Authority holds rights on the Muddy and gets Intentionally Created Surplus (ICS) credits, which they store in the Lake.

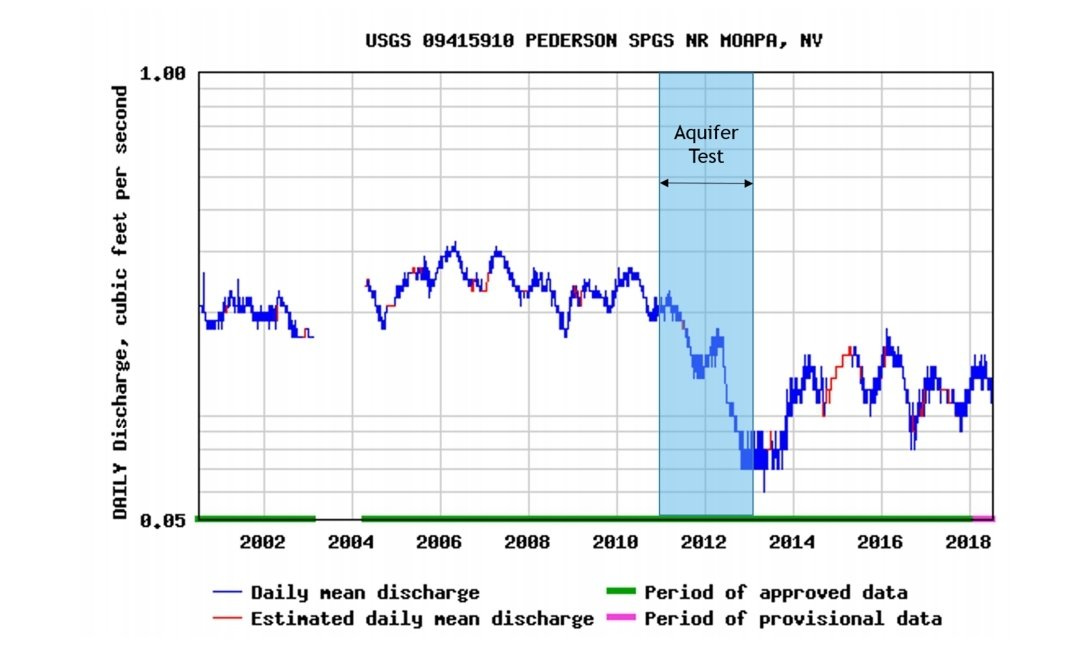

It was long suspected that the LWRFS was composed of a single aquifer system, but in order to obtain further data to justify decision-making about Coyote Springs’ water rights applications, the State Engineer issued Order 1169, requiring Coyote Springs conduct a pump test, to determine the impacts to the groundwater system of their proposed pumping over a two-year period. In just a few months, the impacts from the pump test were severe, and the springs began declining. The State Engineer ended the pump test early.

The evidence from the pump test was evaluated in an evidentiary hearing pursuant to Order 1303 in autumn of 2019. Then in 2020, the State Engineer issued Order 1309, designating the seven basins as the Lower White River Flow System, a superbasin where water would be managed as a single hydrographic unit. The State Engineer also determined a maximum sustainable groundwater pumping amount which would be instated to protect Muddy River flows and the Moapa dace. Finally, the State Engineer explicitly stated that they were relying on the best available science to render these decisions, which sounds like an obvious statement but actually had a significant amount of legal intrigue associated with it.

Litigation

Everybody sued. Coyote Springs and their lackeys sued, of course. The agricultural water users downstream in Moapa Valley sued. The methane gas power plant owners sued. The landfill sued. The gypsum mine sued. The Southern Nevada Water Authority sued, claiming there was still too much pumping. And, in one of those quirks of Nevada water law, we also sued, agreeing with SNWA that too much pumping would continue under the proposed cap.

District court briefing and arguments was a sort of tortured affair. With so many parties (up to 17 parties in the litigation, depending on how you’re counting), with dozens of volumes of testimony and evidence from the Order 1303 hearings, with nearly all of the power players in Nevada water politics involved, this was truly one of the more complicated pieces of water rights litigation in the history of the state. Unfortunately, District Court Judge Bita Yeager was swayed by our opposition, and she overturned Order 1309. Her ruling not only would have given Coyote Springs the water they need to move forward, it would have upturned Nevada water law and put the State Engineer decades behind in trying to manage interconnected sources of water in an increasingly arid world.

So we had no choice but to appeal to the Nevada Supreme Court. As did just about everyone else. What was different for us on appeal, however, is that this time we were siding with the State Engineer in defending Order 1309. While we still have some concerns about the overall pumping limit, our chief principle at the Supreme Court was to defend the Order 1309 precedent, which affects not just Coyote Springs and the Moapa dace but every significant water rights case we would ever bring in the state of Nevada. Order 1309 was groundbreaking in many ways – letting it die would be a huge victory for water developers and speculators and the real estate industry and mining.

So we did what we had to do and appealed to the Supremes and our co-appellants were the Southern Nevada Water Authority, the Muddy Valley Irrigation Company, and the State Engineer. Back during the SNWA pipeline proceedings, when we and Great Basin Water Network and the anti-pipline coalition were locked in holy war with SNWA over the future of water in eastern Nevada, we always talked about the virtues of “strange bedfellows,” referring to environmentalists and ranchers working together. And it was revolutionary. But now, fast forward, you want strange bedfellows? The radical lefty litigious environmental group and the municipal water supplier for Sin City… now THAT’S strange bedfellows!

I’ll spare you the details of the Supreme Court proceedings other than to say that Coyote Springs’ counsel did them no favors during oral argument, making sweeping statements about Nevada water law that those in the audience felt couldn’t be substantiated. And that the Court took great pains to limit the amount of testimony and briefing, restricting the frame of analysis to the legal underpinnings of Order 1309. In other words, we weren’t arguing about whether there was enough water for Coyote Springs – we were arguing about whether it was legal or not for the State Engineer to make such a determination and take action based on it.

The Ruling

We won. An unequivocal, unqualified, complete victory on all of our claims.

About six months after oral arguments, the Nevada Supreme Court issued a unanimous ruling and we won on nearly every point we argued. In an unusual approach, the Court made many very definitive statements about Nevada water law, leaving no ambiguities and no room for questioning. It was very different from how they normally approach rulings like this. Rather than a narrow ruling that only deals with the questions at hand, they put forward an extremely expansive ruling that has precedential value over literally every single water rights dispute this state will deal with for decades to come. Some samples of their remarkable language:

“We hold that the State Engineer has authority to conjunctively manage surface waters and groundwater' and to jointly administer multiple basins and thus was empowered to issue Order 1309.” (p. 7)

“If the best available science indicates that groundwater and surface water in the LWRFS are interrelated and that appropriations from one reduces the flow of the other, then the State Engineer should manage these rights together based on a shared source of supply. Since the State Engineer must have the ability to conjunctively manage and jointly administer water across multiple basins in order to prevent the impairment of senior vested rights under NRS 533.085, we hold that he has the implied statutory authority to do so.” (p. 17)

“statutes containing the word "basin" expressly contemplate underground water and thus should not be limited to solely a surface level or topographical meaning.” (p. 20)

“the clause enabling the State Engineer to "make such rules, regulations and orders as are deemed essential for the welfare of the area involved" is a broad delegation of authority, one that encompasses the creation of the LWRFS out of multiple sub-basins for future management and determining the maximum amount of water that can be pumped…” (p. 24)

So the Supreme Cort overturned the District Court and upheld Order 1309. Their major findings which will ripple across Nevada water law for decades to come:

The State Engineer may “conjunctively” manage surface and groundwater as a single resource. No further ambiguities about this.

The State Engineer’s authority to manage surface and groundwater as a single resource is implied by his clear statutory duties to protect senior water rights and wildlife.

Hydrographic basins established in the 1960s with a limited knowledge of Nevada’s structural hydrogeology are not immutable but in fact must be revised and delineated based on our current best knowledge of the interconnectivity of aquifers.

The best available science must guide the state engineer’s decision-making.

The state engineer must manage future water appropriations to protect values that are in the public interest, including wildlife.

These are the very topics we’ve been fighting about in the courts and in the legislature for many years – I’ve been here fighting about them for 7 years but it’s been going on a hell of a lot longer than that. Ultimately, our fights over the SNWA pipeline and AB298 in the 2017 legislative session and AB30 in the 2019 legislative session and AB387 in the 2023 legislative session – they were all revolving around these questions.

Almost every source of surface water in the valleys of the state of Nevada has some connection to groundwater. Across over 1/3rd of the state, every significant spring is derived from the large carbonate aquifer that underlies a huge swath of the Great Basin from Salt Lake City to Death Valley. In areas without the carbonate aquifer, there are still localized aquifers which transmit water from snowmelt in mountain ranges to valley bottom springs and wetlands. In the wetter northern part of the state, rivers and creeks have interconnectivity with shallow alluvial aquifers. Outside of the creeks that flow directly from snowmelt in the mountains, if you have surface water in Nevada, there is definitely a groundwater connection.

And that means there’s conflict. For about a century, people have been pumping groundwater as if it were a totally discrete resource from nearby surface water. All across the state, surface water resources have been impacted by groundwater pumping. Whether this is valley-bottom springs going dry adjacent to center pivots or mine dewatering; whether it’s declines in creek and river flow after pumping for residential sprawl; whether it’s a whole river system collapsing under the weight of massive overappropriation of groundwater… This conflict is totally pervasive, affecting everybody.

So this ruling will therefore influence practically everything the State Engineer does. Every water rights dispute or case that involves groundwater pumping in basins with surface water rights. It will prove significant for wildlife and environmental advocates, who will invoke the precedent in urging the State Engineer to act to protect ecosystems, and in defending the State Engineer in court when he does act. It will prove significant for senior water rights holders on surface springs, creeks, and rivers, who will now be able to potentially pursue conflict determinations with nearby groundwater pumpers, even if those pumpers are located in a different valley. It will prove significant for community water supplies, mining companies, real estate developers, irrigators, Tribes, the whole universe of the Nevada water world.

Winners and Losers

There are a lot of ways to look at the winners and losers from Sullivan v. Lincoln County, both in the literal sense from the case, and in the ramifications of the precedent going forward.

First, the winners. Our co-plaintiffs, the Southern Nevada Water Authority, the Muddy Valley Irrigation Company, and the Nevada State Engineer, worked with the Center to convince the highest court that we were indeed correct. SNWA and MVIC were represented by the formidable Paul Taggart, who has his hands in nearly every significant water issue in the state. The state was represented by Deputy Attorney General James Bolotin, among others. The Center’s Nevada staff attorney Scott Lake represented wildlife and the public interest. Congratulations to the attorneys and the hard hours they put in on this.

One obvious winner from the ruling is the Nevada State Engineer. He now has the highest court in the land certifying that actions he has already been taking for conjunctive management are not only legal but encouraged by state law. He now can start to administer groundwater basins with a single source of supply as a single hydrographic unit. A big deal to start resolving conflict between users, as well as with environmental values. He can now rely on the best available science as a matter of law, not just a statement of dubious import in a legislative declaration.

SNWA’s a winner: they have their Muddy River water rights, and thus ICS credits, secured. Since the Muddy River is discharging fossil water from the carbonate aquifer, its discharge remains fairly constant despite changing climate and precipitation. This is a reliable source of drinking water for Las Vegas, some 30,000 acre feet.

As for the Center, our interests in the protection of ecosystems and endangered species habitat are clearly winners. If pumping increases in the LWRFS, as Coyote Springs proposed, the dace could go extinct. This ruling will prevent that, assuming the rest of the case goes our way.

And the losers. It’s quite a motley crew. Lincoln County Water District & Vidler Water Company; Coyote Springs; Nevada Cogeneration Associates; Apex Holding Company; Dry Lake Water Company; Georgia-Pacific Gypsum; Republic Environmental Technologies. Spanning the whole panoply of extractive users of groundwater in the LWRFS. Their interests are not uniform. While, after this plays out in court, some of them stand to lose water; not all of them do. Some ironically could come out on top with their water rights even more secured.

Coyote Springs, on the other hand, is a definite loser here. They do not have water to build their city. They still have another bite at the apple in court, where they will argue that Order 1309, even if legal, was not based on substantial evidence. But we feel very strongly about our prospects in that phase of the case. So they’re likely out of options, should they lose that round. While at one time Coyote Springs was favored by the political class, it has new owners right now who aren’t favored by the local political class, who now views it as a nuisance. I genuinely believe this city will never be built.

Other losers include Lincoln County and infamous water speculators Vidler Water. Vidler, now owned by DR Horton Homes, acquired significant water rights in Lincoln County. While their exact intentions are unknown, it was speculated those rights could be sold downstream to Coyote Springs and other developers in Moapa Valley. This includes their water rights in the remote Kane Springs Valley, which we had to fight to include in the LWRFS. Ultimately, the demise of Coyote Springs would mean the loss of Lincoln/Vidler’s best prospect for a customer for that water. They also could subsequently lose some of that water in LWRFS proceedings to come.

So there’s definitely winners and losers of Sullivan v. Lincoln County. But what about the winners and losers of the precedent going forward? That question is much more tricky. Since conjunctive management affects everyone, and since every industry has some amount of senior surface water rights, it will affect every situation differently.

The Humboldt River is one place where that dynamic will play out. Groundwater pumping in the Humboldt River Basin, by irrigators and by mine dewatering, dries out the river and prevents water from reaching senior water rights holders in Pershing County. This ruling likely gives Pershing County new ammunition with which to compel the State Engineer to deal with overappropriation in the Humboldt River Basin. But who will lose their water so that Pershing can be made whole? The answer will span industries and geographies.

Senior water rights holders get a mixed bag from this ruling. Senior surface water rights holders are almost universally going to be winners from this ruling, having their right to defend their surface water from impacts due to groundwater pumping enshrined in precedent. Senior groundwater rights holders, on the other hand, may find their rights subject to new limitations based on potential impacts to surface water. There are likely a dozen more steps that would have to happen before that scenario came to pass, more court cases, more rulings. But the chain of events starts with Sullivan v. Lincoln County.

Wildlife is a winner. The State Engineer has long held the ability to manage water for the protection of the environment, including wildlife, by categorizing such a concern within the framework of the “public interest.” Nevada water law prevents the State Engineer from authorizing water uses that negatively affect the public interest. The State Engineer holds that killing off wildlife or destroying ecosystems is against the public interest. This case is one of the most prominent applications of that doctrine, and it was upheld by the Supreme Court. And the Court took it one step further, finding that the State Engineer can take significant management actions to regulate future appropriations in order to prevent harm to the public trust, i.e. wildlife.

Now, in one sense, the Center for Biological Diversity are losers here, inasmuch as the Court didn’t really address one of our primary concerns all along – the interaction between the LWRFS and the Endangered Species Act. We had argued that the state is obliged not to violate the Endangered Species Act by permitting water uses that harm endangered species, and the State Engineer agreed in Order 1309. In Sullivan, the Court didn’t directly address this argument, but did say that existing water rights could not be reapportioned based on attempts by the State Engineer to comply with the ESA. So in that sense, it limits the application of the ESA within the context of the Sullivan precedent. However, the Court did us one better. Instead of recognizing the ESA as a controlling factor on the State Engineer’s actions, it recognized wildlife in general as that factor. So we don’t even need listed species to challenge water applications that would harm wildlife! Excellent! So in that way, we, and our conservation descendents, water warriors decades from now, are all winners because we’ve gained a valuable tool to defend wildlife and ecosystems.

One winner from this outcome is former Division of Water Resources Deputy Administrator Micheline Fairbank, now working at Fennemore Craig. Micheline was really the architect of a lot of the State Engineer’s LWRFS strategy over the past decade or so, under 3 State Engineers. She masterminded rulings that pushed the envelope of the State Engineer’s powers, defended them in court, and engaged in the legislative session seeking lawmakers to codify these powers. She was at times our foe, but in the LWRFS we were allied. I’m sure she felt pretty good about this ruling, as vindication for a very lengthy project.

Another winner from this ruling is former DCNR director Brad Crowell, now a commission on the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. After it became clear we were going to prevail on AB30 in 2019, Mr. Crowell got the legislature to pass what we quietly called his “consolation prizes”: two legislative declarations in NRS 533.024. 533.024(c) provides that the State Engineer is “encourage[d]” to “consider the best available science in rendering decisions,” and 533.024(e) says that the policy of the state is “to mange conjunctively the appropriation, use, and administration of all waters of the State, regardless of the source of water.” Because these were simply legislative declarations and seemingly not full statute, most people basically ignored them. But not the State Engineer. The State Engineer took these declarations as law and acted accordingly. Everyone was skeptical. But the Supreme Court agreed with him. They said that the declarations support the State Engineer’s “implied statutory authority,” to conjunctively manage surface and groundwater, and thus he may act accordingly. This could actually have ramifications for the interpretation of any number of legislative declarations throughout the NRS. Kudos to Mr. Crowell for his foresight, which we all pooh-pooh’d at the time. I'm eating crow.

What’s Next

The court did not end the case. Coyote Springs, like the poor beplagued commoner in a Monty Python sketch, is not dead yet. At the district court, Judge Yeager first examined whether Order 1309 was legal, that is, did the State Engineer have the authority to issue Order 1309? Since she found that he did not, she did not move on to the second part of the litigation, which would be assessing whether or not the State Engineer relied on “substantial evidence” to render his decision. The Supreme Court was ruling on the first matter- the authority and legality of issuing Order 1309. Now, they have remanded the case back to the District Court to conduct the substantial evidence portion of the litigation.

We feel quite confident about our prospects of withstanding the substantial evidence test. Most hydrologist agree – pumping in the LWRFS will affect the Muddy River. There’s very little disagreement about that outside of hydrologists in the employ of Coyote Springs and their lackeys. So, let’s have at it. We’re sure that Order 1309 will hold up in a substantial evidence test. And then, truly, we can drive the nails into Coyote Springs’ coffin.

There’s also the broader prospect – where will we go to try to protect wildlife and ecosystems from overappropriation of groundwater resources using the Sullivan precedent? Well the Amargosa River is the obvious place. More on that soon. Railroad Valley. The Upper White River perhaps? There are deep carbonate flow systems across the state with imperiled species and too much groundwater pumping. The world is our oyster in a post-Sullivan world.

In the meantime, we’ll gear up for the next phase of the case and make a toast, to a ruling that will echo through the ages. Pushing Nevada water law toward conservation.

Well I’ve said a mouthful so I’ll leave it there.

Keep on down that long and dusty trail,

-Patrick

Without water all is lost. I appreciate your explanation of the case.

Thanks for the excellent presentation of the case. As an attorney I appreciate your command of these issues and the ease with which you discuss them. Congrats on the big win.