Sage and Sand: Upon the Gears and Levers

Wounded people fighting for a scarred land, throwing themselves upon the apparatus to slow the inexorable march of the odious machine

Greetings friends. A considerably delayed interval between publications is attributable to BLM throwing not one, not two, but three NEPA comment deadlines for mining in the southwestern Nevada/California borderlands simultaneously. It’s been a mad dash around here, coordinating a half dozen attorneys, a dozen scientists, numerous advocates and community members; all while trying to remember to sleep and eat and keep up a very rigorous travel schedule. I’ll tell you what, this job is never boring.

A more personal missive this time, short on the news and long on reflection. I’m told people prefer my reflective pieces to my link-dumping anyway, so perhaps that’s the direction things should go in. As always, your feedback is welcomed. Note: names have been omitted intentionally.

Now, without further adieu…

All across Nevada I saw the scars. On a recent road trip across the state I was guiding, the presence of mining was ubiquitous. The scars of open pits, abandoned and filled with toxic water. The scars of stripped hillsides and piles of tailings and heap-leach pads. The scars of exploration wells and roads cross-crossing the desert. The scars of boom-and-bust communities busted down. The scars of so much land, so much wildlife habitat, so much sacred cultural land, so much water, laid to waste by industry.

I also had occasion for the first time to visit Thacker Pass. PeeHee Mu’huh. The rotten moon. Site of a massacre of indigenous people. A place they collect plants and medicine and food. A gathering place. A biodiverse landscape with some of the best sage-grouse habitat across the entire range of the species. Rich sagebrush shrublands. Flowing creeks with Lahontan cutthroat trout. Endemic invertebrates. Thousands of years of humans and the land – living off of one another, sustaining one another.

Now it’s going to be a lithium mine. One lawsuit persists. We met the rancher who is suing to protect his water rights, fearing that his sub-irrigated pastureland will dry up and blow away in the wind due to the mine’s pumping. But the construction proceeds apace – earth moving – and they blasted a pipeline through the hills to the pumping stations. It’s now a wound on the land, a wound on this special place. A wound that won’t scar over for some time as it gets bigger and deeper and more severe. A wound that won’t heal in our lifetime or in many lifetimes.

I’d never visited. My organization was not involved in the fight against the Thacker Pass Mine. We were already knee-deep in Rhyolite Ridge when Thacker got legs and we never turned our attention northward. So it was good to finally lay eyes on it, which has become one of the defining touchstones of the conflict over our renewable energy future.

I got a chance to meet a member of the People of Red Mountain on my travels, the indigenous group fighting to save Thacker Pass and McDermitt Caldera. I talked to one local resident who had heard of half a dozen mining projects proposed for the Caldera. Of false promises of conservation from mining companies. Of a proposed uranium processing plant just outside her home of McDermitt. About McDermitt – her community – how it will always be her home no matter where she goes. About how she is facing its destruction but not taking it lying down.

Desert personage Chris Clarke, most recent of the 90 Miles From Needles podcast, once wrote something that has stuck with me for years. He said, we all know people “who take the existence of a scar for license to reopen the wound.” That scars and wounds on the landscape may beget more scars and wounds. He wrote,

“I am learning that each of us — human, plant, animal, landscape or nation — is a palimpsest of scars laid one atop the another. That suffering cannot be allowed to justify more suffering. That lashing out under remembered pain may cause the wound that prompts someone else to create a wound in yet another person.”

I’ve got scars. Scars from a catastrophic rock-climbing accident – bones that didn’t mend right. Scars from various childhood mishaps. Scars on my lungs from devastating illnesses, pneumonias, COVIDs; from decades of self-inflicted abuse. Scars on my leg from a rock tumble on a remote desert peak that could have been a whole lot worse, but I got lucky and only had a bad set of stitches from a shitty urgent care clinic in Pahrump. And then the unseen scars. Far worse, far poorer healed. Best not to get into those.

This beautiful desert, like me, is a collection of scars. But one scar should not be sufficient to write off a landscape. Thacker Pass should not be sufficient to justify destroying the entire McDermitt Caldera. There is still wildlife there; still a wild ecosystem there; it is still the cultural landscape of the indigenous people there, mine or no mine.

I think of Yellow Pine Solar in Pahrump Valley near my home pretty similarly. As I’ve stated, one of the great regrets of my life is failing to intervene on this project. Smack dab in the heart of one of the largest remaining undeveloped and unprotected landscapes in the Mojave Desert, Yellow Pine has destroyed the homes of hundreds of desert tortoises, broken connectivity, and provided a foothold for industry which is now looking to metastasize across the valley. There are ten solar projects proposed for Pahrump Valley. It would be an utter catastrophe for local biodiversity. The Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed removing the entire thing from solar development.

The wound on the land from the one solar project is not sufficient justification to offer up the whole rest as a sacrifice zone for clean energy. And it’s not sufficient justification for advocates to write off the valley. I may have messed up with round 1, but I’m not going to mess up again. I’ll do whatever I can protect Pahrump Valley, scar or no scar. It’s still the Amargosa Basin. It’s still my home. It’s scarred like I am.

I met a man, an indigenous elder, who whether he was just making idle conversation or he wanted to lay some wisdom on me, gave me things to think about which still dwell in me weeks later. “You’ve got to know where you come from,” he told me. “The problem is that nobody knows where they’re from.”

This is such a fraught question for me. Where do I come from? I say, pretty unequivocally, that I’m from the desert. I wasn’t born and raised here, of course. I was born in New York, raised in Connecticut and New Jersey. My parents were from the Midwest, my family roots are in four different Southern states. I left the East when I was 20. I sold most of shit, packed the rest into my 1991 Chrysler LeBaron convertible and pointed it West. I always knew I wanted to land in California – Jack Kerouac and the Grateful Dead fueled my young, vulnerable brain. And by the time I landed an internship in Joshua Tree in 2004, my life course was set.

But it was only 10 years ago that I first found my home. I remember meeting the Shoshone pupfish; hearing phainopepla’s plaintive cries in the wetland; my first trip to the River downstream from China Ranch; my first date shake; my first trip to Ash Meadows with our hydrologist, starting to learn about the vast rivers of heated water flowing deep underground beneath my feet; my first visit to beautiful Twelvemile Spring and finding lithics and grinding stones; my first Death Valley spring bloom. I was hooked very quickly, and I’ve been here ever since. I’ve tried moving away twice, only to come rushing back in months. This is the only place where I’ve ever thought that I want to spend the rest of my life in. It’s home.

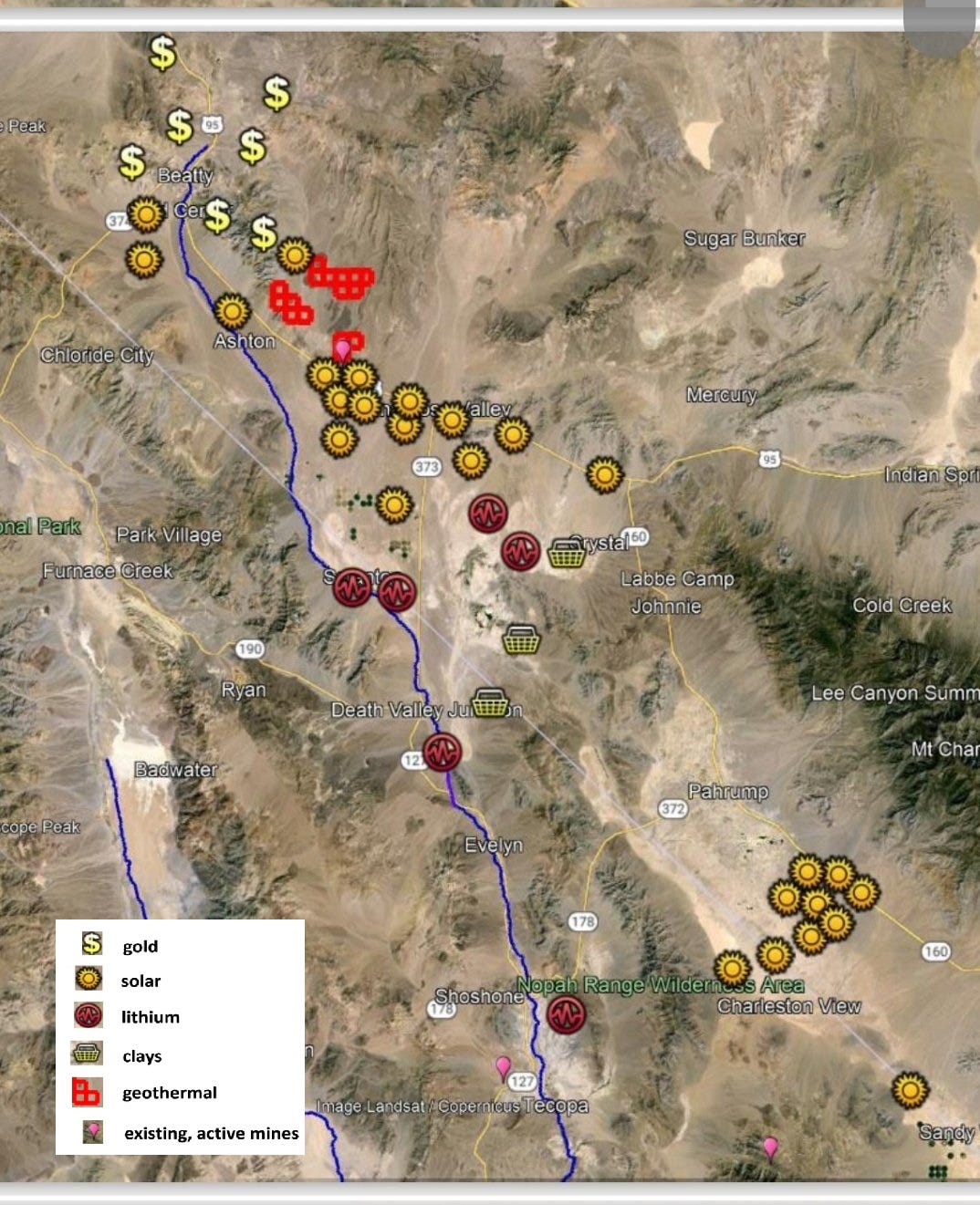

When I look up and down the Amargosa River Basin, I’m horrified. 25 solar projects, 8 gold mines, 4 lithium mines, 4 clay mines, 1 wind project, 10,000 acres of geothermal leasing, and the nation’s nuclear waste dump, all proposed for this: one of the most biodiverse watersheds in North America. It’s a horror show that permeates my whole being. It’s the sword of Damocles hanging over the head of all of us who call this beloved Basin home.

The Amargosa is scarred, sure. Historic mining has a legacy here. Ghost towns and small pits and adits and shafts and tailings piles seemingly everywhere. Their scale pales in comparison to modern day mining operations, but they’re there. But the Amargosa is scarred like we’re scarred. And we are still resilient. She with her abundant endemic biodiversity that is hanging on despite the odds. Our little community tenaciously clinging to an anachronistic way of life in an area inhospitable to most conventional ways of living.

One solar project is not a reason to give up this beautiful place, and I have not. One lithium mine is not a reason for the People of Red Mountain to give up on their home in McDermitt Caldera, and they have not. One dozen or a hundred mines across the Great Basin aren’t a reason to give up on this beautiful place, and we have not. We will not.

Upon the Gears and Levers

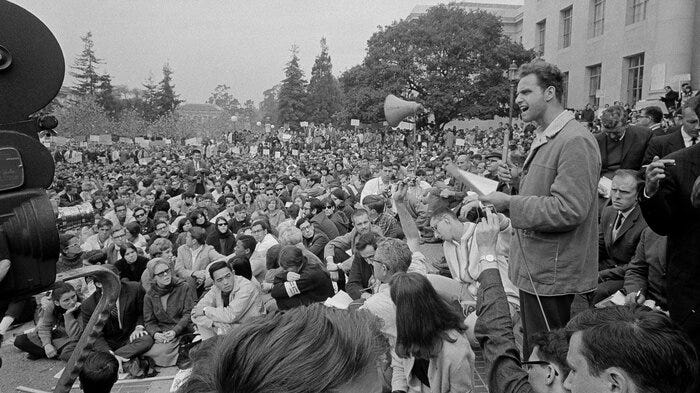

“There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part! You can't even passively take part! And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels ... upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to make it stop! And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!”

Mario Savio said those immortal words on the steps of Sproul Hall at the University of California-Berkeley in 1964, a speech that was a touchstone moment during the Free Speech Movement and an early incarnation of 1960s activism. I think about those words frequently, as I’m trying to figure out how to fight back against the extinction machine. But they have reverberated in my skull for weeks now as a busy Spring season has taken me across the Great Basin and has intersected dozens of people putting their bodies upon the gears.

There is a resource extraction boom in the Great Basin and northern Mojave Deserts, the likes of which has not been seen in decades. Lithium and gold and copper mining; solar energy and geothermal energy; transmission lines and pumped storage; water speculation; pinyon-juniper deforestation for biofuel; it goes on. Advocates from across the region and beyond are working their tails off to try to halt the relentless push to industrialize one of the last, best places in North America. Or at least to identify those places that we care most about and hold the line there.

What does it mean to put our bodies upon the gears and the levers? How do you prevent the machine from working at all – especially in the face of a machine that is the rapacious global demand for energy and minerals backed up by billions in government subsidies?

Savio was addressing a group of occupying student protesters, who were literally putting their bodies on the line, preparing to be arrested. There’s a pretty mixed track record of civil disobedience and arrest materially affecting the outcome of mining and energy projects, at least when it’s not in the context of a mass movement.

So how else might we put our bodies upon the levers? Through my travels this Spring I’ve had so many opportunities to meet and share strength with advocates who are putting their bodies upon the gears and wheels and levers and the whole apparatus in so many ways.

I’ve encountered indigenous activists who are fighting for their ancestral lands and waters. People who drove hundreds of miles to see and experience Rhyolite Ridge and attend the public meeting in Tonopah to show their solidarity against the destruction of these lands. I’ve spoken with Tribal Historic Preservation Officers, working feverishly to keep up with a deluge of letters from BLM, informing them of yet another project which will harm their ancestral lands and cultural landscapes. I’ve visited with tribal members with a long, deep history and sense of place for the places at risk who showed me secret places I never would have found on my own – springs and seeps that are the epicenter of life in our beautiful desert.

I’ve spent time with old friends who are trying desperately to achieve permanent protection for one of their most sacred sites – Bahsahwahbee, the Sacred Water Valley, what we call Spring Valley in eastern Nevada. They are so close. Decades of work are almost at a culmination... as long as obstructionist bureaucrats step out of the way.

I’ve also gotten to hear from indigenous advocates who are telling the tale of cumulative, generational harm from mining: the contaminated waters, the cancers and deaths. They are sharing their pain so that others might learn.

I went on a 1,000-mile mining tour with advocates from around the country who didn’t come from a background of opposing bad mining projects; their background is supporting a just energy transition off of fossil fuels while respecting workers and the environment. They endured a thousand miles in three days, visiting numerous sites at risk of mining for energy transition minerals and witnessing the legacy of decades of mining’s impacts. They are trying to change how our energy transition moves forward – helping to nudge the course of an enormous ship as it careens toward an uncertain energy future.

I’ve been hanging out with groups of scientists who are documenting the biodiversity at risk from resource extraction. One young botany student and her compatriots who are surveying an area under risk of becoming a whole ass mining district (not just one mine), have already documented a new state occurrence of a rare and iconic plant. These dedicated scientists turned out in a remote central Nevada town to register their objections to a mine which threatens biodiversity. Some of them are writing expert-level reports to help us evaluate the claims in the mine’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Their data may help to transform the regulatory landscape for mining in these biologically sensitive areas. Or it may add to our heartbreak as we see places lost. They’re putting their bodies on the levers and gears literally – clambering over rocks and cliffs; and otherwise, writing and cataloguing until the wee hours to make sure the data is there.

I got to while away some hours with old school water activists, folks who have been fighting these battles since before I was born. Being on the board of the Great Basin Water Network and part of the coalition that successfully killed the Las Vegas pipeline is one of the great honors of my life. Our biannual in-person meetings at the spiritual home of the organization in Baker, Nevada are soul-cleansing and heart-nourishing. These folks, all volunteers, have dedicated their lives to water, and now their legacy is being magnified by the dedicated work of their executive director. They have put their bodies upon the wheels for decades, grinding projects like the pipeline and the MX to a halt. Now they’re helping the next generation find out how to gum up the works.

I spent a few days on the Gila River in southwest New Mexico. This isn’t up in the more famed Gila Wilderness, which is a forested montane area. No, this was down in elevation, in the lower Chihuahuan Desert transition zone. The area was in a rich spring bloom for our visit, and I identified over 40 species of blooming flowers. I saw a Gila monster and southwest willow flycatchers. And I got to spend time with two activists, two dear friends, who can turn it off with me and just enjoy each other’s company and the natural silence. They put their bodies on the whole apparatus on a daily basis, working with abandon and sometimes without regard for self-care, enabling scores of people to go forth and do the work from their leadership positions. I’m so lucky to have such inspiring mentors and friends.

I’ve spent time with paid environmental advocate professionals. Attorneys and scientists and organizers and lobbyists and comms. Folks who, yes, get paid to do this work, but work with a fierce dedication that goes well beyond whatever compensation they receive. Long hours, nights and weekends, doing what it takes to meet the deadline, to crank out the report, to file the brief, to file the preliminary injunction, to talk to the reporters, to issue the press release. These are my people, and they are putting their bodies on the levers through dedicating their lives, sometimes at the expense of their wellbeing, to the fight.

And with all of these people, the common thread is caring about something other than themselves. Other than money. The land, the water, their homes, their families, their communities, their culture – these are what motivate these folks. Not money, not fame or notoriety, not ego. Love of place, love of people. Love of water and life.

So, we go about our business as wounded people fighting for a scarred land. And our wounds and scars and its wounds and scars eventually meld into one. And we are from the land, and we are made of water. And in the end, we are just the land and the water fighting for themselves. We are following spiritual instructions beyond our comprehension, driven by something we cannot understand – the earth and the water made manifest in devotion. We are putting ourselves on the gears and levers, shutting down the whole damn apparatus. Wounded we will continue through this world, scars be damned. It’s on us to see this through.

Stick with it, my friends. While there are darker days to come, we are united in our struggle.

Keep on down that long and dusty trail,

-Patrick

Great article. I live in NYS, but became familiar with Thacker Pass a couple of years ago when someone involved in that fight asked me to write an article on it. It's a tragic situation on many levels, a project that should be stopped based on water requirements alone, and as usual makes victims of the poorest and already victimized. This push for Green Growth is a giant lie. Renewables can never power the destructive economy we're accustomed to, anyhow. We are destined to degrow one way or another. https://geoffreydeihl.substack.com/p/showdown-at-thacker-pass

Beautiful writing, Patrick. I am glad to hear there are so many people putting up a fight and I only hope we can increase their numbers!